For some especially twisted individuals, the arrival of autumn is greeted warmly, as a reprieve from the oppressive summer heat. Among those who subscribe to this mindset are the members of Bon Iver, as they bring their “autumnal” album on the road for a string of arena dates across the country. This year’s i,i came fast, in relative terms, on the heels of 2016’s pissed off and garish summer fever dream, 22, A Million. It’s a corrective and magnificent album that feels like a cooling of heads. It’s warmer, more self-assured and precise than the springtime frost of its calendar inverse—2011’s Bon Iver, Bon Iver. And, while lightyears away from Bon Iver’s snowy For Emma, Forever Ago folk origins, the afterglow of that album’s acoustic strums are once again visible in i,i’s influences—no longer as obscured as they were on 22, A Million. Armed with a renewed capacity for enjoying life, and a state of the art three-dimensional sound mapping PA system, Justin Vernon & crew were prepared and energized to bring their new album’s saturated sonic fall foliage to Boston’s TD Garden.

The concert was opened exquisitely by Feist, the next artist up for a tour where support has been provided by a series of indie rock institutions, like Yo La Tengo and Indigo Girls, all of whom make—and I say this lovingly—music to soundtrack an older millennial dinner party. Leslie Feist was a commanding presence on stage, eschewing the likes of twee single “1234”— fit for a more optimistic time and place—in favor of the swelling and theatrical side of her catalog, exemplified by 2011’s Metals. Though best known for her alternatingly breathy and bellowing voice, Feist showcased her underrated skill as a virtuosic and percussive guitar player. Concluding her opening set with an arena-sized rendition of 2004’s “Let it Die” and many sincere thank-you’s, Feist—ever a fountain of gratitude and optimism cut from the same moral fabric as her brethren in Broken Social Scene—adds credence to the idea that longevity as a performer comes from fantastic songwriting backed by an ethos.

How fitting that Feist—whose music sounds like being in love in winter time, preceded an artist most famous for an album about falling out of love within the doldrums of a snowy cabin. Bleak as that sounds, if you know anything about Justin Vernon, you may find him to be a well-adjusted pillar (or “blobtower,” as his Twitter handle lampoons) of joy and steady-handed sincerity. Vernon is at once a broad-ranging auteur eating Flamin’ Hot Cheetos with Chance the Rapper, and a hinterlands-oriented agoraphobe who just prefers the simplicity of things in the woods of Wisconsin. A burgeoning Deadhead with Hornsby-approved bona fides who sat in for an impromptu jam sesh with Dead & Company on LSD. A sensitive jock made good. You can imagine him telling you about Carole King songs that make him cry without a trace of irony, and just as soon fist bumping you on his way out the door. In short, the man contains goddamn multitudes.

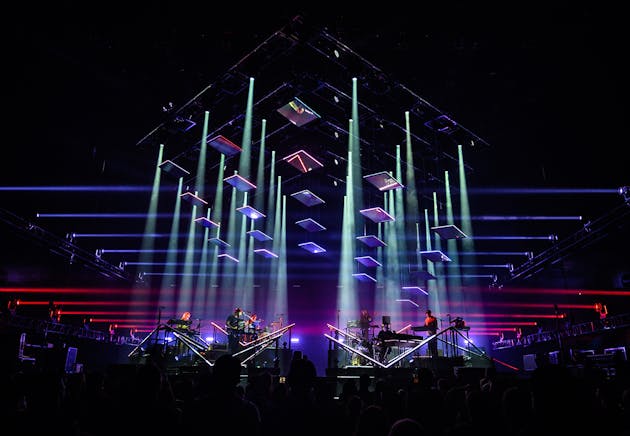

At 9pm sharp, the aforementioned next-level L-ISA Immersive Hyperreal Sound system fluttered the brick-crushed samples that open i,i around the arena with immense fidelity. Notably, the difference between a cluttered traditional arena sound system and Bon Iver’s proprietary solution was stark. The vocals and snare drum in particular seemed to occupy a separate plane, making for immersive and satisfying clarity. As an appropriate complement, the visual effects of shifting mirrors and a light show synched perfectly to every tom hit and sample trigger nearly stole the show from the musical performance. It made for a rare indie rock-adjacent concert where closing one’s eyes, even momentarily, would detract greatly from the experience.

The band emerged and took their places each in their own glowing chassis and began their set in strict adherence to their new album’s tracklist. It’s hard to imagine a tender line like “I like you / I like you / And that ain’t nothing new” from this year’s “iMi” having a place on Bon Iver’s last offering, but this welcome rediscovered thoughtfulness from Justin Vernon set the tone for the remainder of the concert. After the primal shuffle of “We,” and the polka-dotted contemplation of “Holyfields,” the band relented on new material and turned to their vaunted back catalog with a trodding “Touch of Grey”-era Grateful Dead-esque rendition of 2011’s “Perth.” Vernon alone delivered a pained and emotionally auto-tuned belting of “715 - Cr∑∑ks” like some sort of chopped and screwed Phantom of the Hockey Arena; but of course, for an artist sometimes mistakenly thought of as a solo act, it was the backing of his band that really added depth to the performance. The inimitable Jenn Wasner of Baltimore-based indie duo Wye Oak provided strong harmonies where Vernon’s falsetto strained to reach. Drummers Sean Carey and Matthew McCaughan colored a maximalist version of fan-favorite “Blood Bank” with an outrageous drum outro. Interestingly, “Skinny Love,” the unlikely avalanche of an indie hit that soundtracked countless Obama-era break-ups, was performed by Vernon alone à la For Emma—a divergence from its recent full-band years.

Towards the end of the set, Justin Vernon thanked the audience for making an arena show possible for the likes of his band, quipping correctly that they aren’t the sort of act you usually see in a room of this size. Indeed, despite reports of low ticket sales in various cities across the country on this ambitious tour—the arena was fully packed. That said, it isn’t a stretch to assume that the songs that sold the tickets are largely the lovelorn poetry of For Emma, Forever Ago and the hazy nostalgia trip of Bon Iver, Bon Iver. The crowd seemed largely of the perfect age to have posted high school Facebook photos where basement scenes strewn with pilfered Smirnoff in water bottles live alongside captions like “And at once I knew, I was not magnificent.” But as these fans—thankfully, myself included—grew out of the performative moodiness of youth, so did Bon Iver.

I don’t know if the road of logical growth from fragile folk music leads straight to glitching trap drums and pitch-shifted mega-choir vocals, but it sure feels a whole lot more fresh than an indie band that so predictably and lazily “pivots to synths.” The transition from Bon Iver, Bon Iver—notably, the end of being able to call them a folk band—to 22, A Million’s garbled beauty, was abrupt, reactionary, and likely took a lot of fans by surprise. One gets the sense that i,i, reveals a return to something closer to what Bon Iver probably want to sound like. It works for them, too: it’s less spiteful, less intent on erasure, and more honest with itself—hell, there’s an excellent song on the album about the importance of calling your mom. These are songs that can still live alongside the resonant junkyard strums of “Skinny Love” or “The Wolves.” Taken as a whole, enjoying Bon Iver’s shape-shifting musical identity is predicated on being comfortable with seasonal confusion, like seeing parkas and shorts worn on the same October day, but knowing that both choices may be equally valid to different people just living their lives. Appropriately, at the end of a rapturous encore, Justin Vernon encouraged us all to “spread love,” and on Tuesday night he and his band did exactly that.